- Home

- Robert Alden Rubin

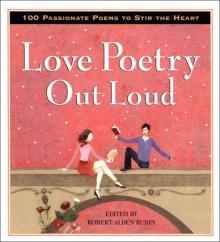

Love Poetry Out Loud

Love Poetry Out Loud Read online

LOVE POETRY OUT LOUD

Edited by Robert Alden Rubin

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

For Eva Maryette, who read to me

THANKS TO

Elisabeth Scharlatt for remembering, and to Kathy Pories, Ina Stern, Bob Jones, Elizabeth Maples, and the crew at Algonquin. Additional thanks to Liz Darhansoff and the patient librarians at the Jefferson Building and at the Enoch Pratt Free Library. And, of course, to that most patient of librarians, Cathy.

“The world swarms with writers whose wish is not to be studied, but to be read.”

—Samuel Johnson

CONTENTS

Why Love Poetry?

1. Silly Love Songs

Litany—Billy Collins

For an Amorous Lady—Theodore Roethke

She’s All My Fancy Painted Him—Lewis Carroll

The Lingam and the Yoni—A. D. Hope

To an Usherette—John Updike

Love under the Republicans (or Democrats)—Ogden Nash

Love: Two Vignettes—Robert Penn Warren

Resignation—Nikki Giovanni

“O Mistress Mine” (from Twelfth Night)—William Shakespeare

Nothing but No and I—Michael Drayton

2. Hello, I Love You

The Good Morrow—John Donne

“Wild Nights—Wild Nights!”—Emily Dickinson

Meeting and Passing—Robert Frost

The Greeting—R. H. W. Dillard

The Light—Common

“The Twenty-ninth Bather” (from Song of Myself)—Walt Whitman

Thine Eyes Still Shined—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Surprised by Joy—William Wordsworth

Love’s Philosophy—Percy Bysshe Shelley

Poem—Seamus Heaney

3. The Comedy of Eros

Pucker—Ritah Parrish

Love Portions—Julia Alvarez

Lonely Hearts—Wendy Cope

“I, being born a woman”—Edna St. Vincent Millay

Love Song: I and Thou—Alan Dugan

Love Song—Dorothy Parker

The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd—Sir Walter Raleigh

Portrait of a Lady—William Carlos Williams

Where Be Ye Going, You Devon Maid?—John Keats

Brown Penny—W. B. Yeats

4. Eye of the Beholder

How Do I Love Thee?—Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Juke Box Love Song—Langston Hughes

To My Dear and Loving Husband—Anne Bradstreet

from Homage to Mistress Bradstreet—John Berryman

Song: To Celia—Ben Jonson

A Red, Red Rose—Robert Burns

Ask Me No More—Thomas Carew

A Girl in a Library—Randall Jarrell

“Not marble nor the gilded monuments”—William Shakespeare

“Not Marble nor the Gilded Monuments”—Archibald MacLeish

5. Loves Me

A Birthday—Christina Georgina Rossetti

Thou Art My Lute—Paul Laurence Dunbar

somewhere i have never travelled, gladly beyond—e. e. cummings

Love Poem—Connie Voisine

The Song of Songs (7:1–8:3)—The New English Bible

“If I profane with my unworthiest hand” (from Romeo and Juliet)—William Shakespeare

Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal—Alfred, Lord Tennyson

When We Two Parted—George Gordon, Lord Byron

“Joy of my life, full oft for loving you”—Edmund Spenser

The Changed Man—Robert Phillips

6. Loves Me Not

Then Came Flowers—Rita Dove

The Defiance—Aphra Behn

A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning—John Donne

When You Are Old—W. B. Yeats

I Will Not Give Thee All My Heart—Grace Hazard Conkling

Neutral Tones—Thomas Hardy

“I hear an army charging upon the land”—James Joyce

Silentium Amoris—Oscar Wilde

Variations on the Word Love—Margaret Atwood

Taking Off My Clothes—Carolyn Forché

7. Pleasures of the Flesh

Wrestling—Louisa S. Bevington

Wet—Marge Piercy

Down, Wanton, Down!—Robert Graves

Poem for Sigmund—Lorna Crozier

Lullaby—W. H. Auden

Green—Paul Verlaine

Coral—Derek Walcott

Her Lips Are Copper Wire—Jean Toomer

“Come, Madam, come, all rest my powers defy”—John Donne

The Aged Lover Discourses in the Flat Style—J. V. Cunningham

8. Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone?

The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter—Ezra Pound

Letter Home—Stephen Dunn

The Voice—Thomas Hardy

I Will Not Let Thee Go—Robert Bridges

The Meeting—Katherine Mansfield

Still Looking Out for Number One—Raymond Carver

Bearded Oaks—Robert Penn Warren

48 Hours after You Left—DJ Renegade

“That time of year thou mayst in me behold”—William Shakespeare

Good Night—W. S. Merwin

9. A Failure to Communicate

Never Pain to Tell Thy Love—William Blake

You Say I Love Not—Robert Herrick

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock—T. S. Eliot

Adam’s Curse—W. B. Yeats

Fire and Ice—Robert Frost

“After great pain, a formal feeling comes”—Emily Dickinson

“Since the majority of me”—Philip Larkin

The Rival—Sylvia Plath

The Lost Mistress—Robert Browning

Sleeping with You—John Updike

10. Second Time Around

“Since there’s no help, come, let us kiss and part”—Michael Drayton

“Sigh No More, Ladies” (from Much Ado About Nothing)—William Shakespeare

Sources of the Delaware—Dean Young

December at Yase—Gary Snyder

Freedom—Jan Struther

Good Morning, Love!—Paul Blackburn

I So Liked Spring—Charlotte Mew

I Look into My Glass—Thomas Hardy

An Answer to a Love Letter in Verse—Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Symptom Recital—Dorothy Parker

Index of Titles

Index of First Lines

Index of Authors

Why Love Poetry?

I gotta use words when I talk to you,” says Apeneck Sweeney, in T. S. Eliot’s verse play Sweeney Agonistes. And when you get right down to it, that about sums up the reason for love poetry.

Of course, you haven’t “gotta use words” in order to love. Anyone who’s had a favorite dog or cat can tell you about mute affection, and anyone whose mother served chicken soup when they were sick in bed can testify that it’s possible to say “I love you” without speaking. But you can convey only so much with a meaning gaze, a scratch behind the ears, or a bowl of hot soup. Sometimes a kiss or a bouquet of flowers won’t do. Sometimes you gotta use words.

It may seem counterintuitive. Love shouldn’t require words. The singer-songwriter Elvis Costello has said that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” an observation that, at first glance, might as well apply to writing about love. After all, love is a feeling—it’s an intangible sensation, an emotion that each person encounters differently. Written words, mere ink stains on sheets of pulped-up cellulose fiber or pulses of current in a magnetic field, just sit there on the page or screen; how can they be anything more than a poor facsimile of real feelings? What’s the point? Why say anything? As Eliza Doolittle complains in My F

air Lady, “Don’t talk of love, show me!”

Still, futile though it might seem, ever since our ancestors in Mesopotamia started marking on clay tablets five thousand years ago, poets have been writing love poems. There must be a reason.

Maybe it’s because words have an undeniable power, and writing them down is a way of storing that power to use at the right moment, the way a battery stores electricity. There’s something uncanny and scary about being able to translate wisdom from the timeless realm of the written word into the here and now of the spoken word. When Prospero, the master mage in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, is ready to leave his magical island of exile, to go back to the everyday world and live a human life, what does he do? He commits his book of spells to the ocean’s depths. Without the book, he is just like anyone else.

Whoever first said, “Sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me,” didn’t quite get it. On an emotional level, words can hit as hard as any stick; when we name things, it gives us a certain psychological power over them. That myths, legends, and sacred stories are full of prayers and spells and names and magic words testifies that words do matter. What you say can become an action just as much as a kiss, a hug, or a slap in the face, even though you’re only making noise with air from your lungs and vibrations of your vocal cords. After all, babies don’t cry just to hear their heads go off—they do it because they want to make things happen.

The love poems that you will find in this book make things happen too. More than just a poem about love, each is an act of love. It may seek to seduce or amuse, to plead or flatter, to inflict pain or express pain, or console, but it’s not just some elegant abstraction. Most of these poems are written as if spoken from one person to another. Obviously the books I’ve drawn upon brim with good love poems that don’t do what I’m talking about—poems that tell stories of love gone bad (or good), philosophical musings on the nature of love, self-portraits of the artist in love, and so forth. But for Love Poetry Out Loud I have chosen to focus on poems that seek to cross the emptiness that separates two people — the gap that must be bridged for love to be shared.

The poems I’ve selected were, with a few exceptions, written originally in English. This excludes some wonderful love poems, but translating a poem inevitably changes it, introducing a third person (the translator) between reader and poet; reciting poetry in its original language is probably challenge enough. In this book’s predecessor, Poetry Out Loud, I argued that poetry is not a different language, but our language—“only stretched, purged of certain habits, intensified by careful choice, made memorable by pattern and rhythm.” That’s true of love poetry too, and the selections here have been further intensified by the nature of what they’re saying. When I tried out each of these poems, reading them to myself, to my wife, and to friends as I compiled this book, I sought to listen for the voices of the poets who wrote them. I hope you will too.

These are acts of love, launched across space and time, imbued with all the magic and power and artistry that the poet can conjure up. I invite you to read them aloud to yourself. If they speak to you, try reading them to your lover, or to the person you wish to be your lover, or to your ex-lover, or to friends who share your loves, or to anyone else they might speak to.

After all, if you gotta use words, you might as well use good ones.

—Robert Alden Rubin

1

SILLY LOVE SONGS

“Anyone can be passionate, but it takes real lovers to be silly.”

—Rose Franken

* * *

FIGURES—OF SPEECH AND OTHERWISE

Why can’t poets just say what they mean? Every harried student of literature has probably wondered why they insist on employing metaphors, similes, and other elaborate figures of speech when plain English would do just fine. Maybe it’s because playing with words and images is fun, for one thing. And, for another, sometimes plain English won’t, in fact, “do”—sometimes the imagination must be summoned up by outrageous images.

* * *

LITANY

Billy Collins

You are the bread and the knife,

The crystal goblet and the wine …

— Jacques Crickillon

You are the bread and the knife,

the crystal goblet and the wine.

You are the dew on the morning grass

and the burning wheel of the sun.

You are the white apron of the baker

and the marsh birds suddenly in flight.

However, you are not the wind in the orchard,

the plums on the counter,

or the house of cards.

And you are certainly not the pine-scented air.

There is just no way you are the pine-scented air.

It is possible that you are the fish under the bridge,

maybe even the pigeon on the general’s head,

but you are not even close

to being the field of cornflowers at dusk.

And a quick look in the mirror will show

that you are neither the boots in the corner

nor the boat asleep in its boathouse.

It might interest you to know,

speaking of the plentiful imagery of the world,

that I am the sound of rain on the roof.

I also happen to be the shooting star,

the evening paper blowing down an alley,

and the basket of chestnuts on the kitchen table.

I am also the moon in the trees

and the blind woman’s tea cup.

But don’t worry, I am not the bread and the knife.

You are still the bread and the knife.

You will always be the bread and the knife,

not to mention the crystal goblet and — somehow — the wine.

* * *

Variations on a Theme

Renaissance love poetry, notably the fourteenth-century Italian love sonnets of Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch), often likened qualities of the beloved to idealized forms from nature and classical culture—skin became ivory, hair became gold wire, and so forth. Ever since, poets have been having fun at old Petrarch’s expense. So does the American poet Billy Collins, in this fond catalog of his love’s virtues.

Litany = A long prayer of entreaties or a repetitive chant or list; here, a litany of metaphors.

Jacques Crickillon = Belgian poet and writer (b. 1940).

Plentiful imagery = Metaphor often draws a logical parallel between two distinctly different things and provides another way of seeing them.

* * *

* * *

Animal Love

“You’re such an animal!” one lover says to another. Ah, but what kind of animal? Theodore Roethke uses the figurative device of simile to offer some possible answers.

Worm = Archaic synonym for snake.

* * *

FOR AN AMOROUS LADY

Theodore Roethke

Most mammals like caresses, in the sense in which we usually take the word, whereas other creatures, even tame snakes, prefer giving to receiving them.

— From a natural-history book

The pensive gnu, the staid aardvark,

Accept caresses in the dark;

The bear, equipped with paw and snout,

Would rather take than dish it out.

But snakes, both poisonous and garter,

In love are never known to barter;

The worm, though dank, is sensitive:

His noble nature bids him give.

But you, my dearest, have a soul

Encompassing fish, flesh, and fowl.

When amorous arts we would pursue,

You can, with pleasure, bill or coo.

You are, in truth, one in a million,

At once mammalian and reptilian.

* * *

NONSENSE AND SENSIBILITY

Love poetry isn’t usually kid stuff. Here are two verses, one written for general audiences and one tha

t sounds as if it were. But, while English poet Lewis Carroll’s nonsense from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is unlikely to provoke awkward questions from most ten-year-olds, the same cannot be said of Australian A. D. Hope’s nursery rhyme for grownups.

* * *

SHE’S ALL MY FANCY PAINTED HIM

Lewis Carroll

She’s all my fancy painted him

(I make no idle boast);

If he or you had lost a limb,

Which would have suffered most?

He said that you had been to her,

And seen me here before:

But, in another character

She was the same of yore.

There was not one that spoke to us,

Of all that thronged the street;

So he sadly got into a ’bus,

And pattered with his feet.

They told me you had been to her,

And mentioned me to him;

She gave me a good character,

But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone

(We know it to be true);

If she should push the matter on,

What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two,

You gave us three or more;

They all returned from him to you,

Though they were mine before.

If I or she should chance to be

Involved in this affair,

He trusts to you to set them free,

Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been

(Before she had this fit)

An obstacle that came between

Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she likes them best,

For this must ever be

A secret, kept from all the rest

Between yourself and me.

* * *

A good character = A favorable character reference.

* * *

* * *

Zero Sum

Love Poetry Out Loud

Love Poetry Out Loud